Distracted Driving

by DICCON HYATT

A New Year's Day 2016 crash on Route 1 killed a 13-year-old passenger who was not wearing a seatbelt. The driver was using his cellphone as a GPS.

The numbers, by themselves, are bad enough. Last year 607 people died in accidents on New Jersey's roads, up from 562 the previous year, according to State Police figures released in early January. It was the third straight year when traffic fatalities increased despite the auto industry steadily manufacturing cars with better safety features.

According to a state Department of Transportation safety report, drowsy and distracted driving was a factor in 42 percent of all traffic accidents that caused serious injuries and deaths. The National Safety Council, a nonprofit group, estimates that 21 percent of all collisions — more than 1 million crashes — in 2010 involved talking on cell phones, and at least 3 percent involved texting. Cell phone use has only increased since then.

It took less than six hours for New Jersey to record its first fatal traffic accident in 2016, and a driver distracted by his phone was to blame.

Raw statistics can’t account for the devastation caused by distracted driving. There’s also the human cost.

It took less than six hours for New Jersey to record its first fatal traffic accident in 2016. Azel Hernandez Vargas, 27, was returning from a New Year’s Eve party and was driving along Dean’s Lane in South Brunswick approaching Route 1, where there is a jug handle intersection. Four other people, a mix of friends and family, were in the car, including his 13-year-old sister, Blanca Hernandez, who was sitting unbuckled in the back seat.

Vargas, who was from Toms River, was lost, and was using his cell phone for directions. News media reported he was using the phone in a hands-free setting, and had placed it on the center console. But even in hands-free mode, the phone proved to be a fatal distraction. As the car approached the Route 1 intersection, it fell down, and Vargas reached down for a moment to pick it up. In the time his eyes were off the road, his Nissan ran a red light at Route 1, directly into the path of a northbound minivan.

The van hit the car broadside, the impact crushing the small sedan and sending it into a utility pole. Everyone was hurt, especially those who bore the brunt of the crash in the Nissan’s back seat. Blanca, the 13-year-old, was taken to the hospital, where she died of her injuries.

As the year wore on, the tragedies continued.

At around 6:12 a.m. on April 19, 2016, Robbinsville school superintendent Steve Mayer was jogging down Robbinsville-Edinburg Road, a rural byway with narrow shoulders, no sidewalks, and a speed limit of 45 miles per hour. He normally avoided the road during his morning runs but was getting back into jogging after dealing with knee issues and was varying his route. He was listening to a sermon on a portable device and had his golden retriever, Gertie, on a leash.

Police have released few details about what happened next. In the early morning gloom, two minutes before sunrise, 1 17-year-old girl, a senior at Robbinsville High School, was also driving down that road. She ran over Mayer and his dog, killing them. She then drove two miles to the parking lot of Pond Road Middle School and there she called 911, according to a press release by the Mercer County Prosecutor’s Office. Prosecutors said she was using her phone at the time of the crash. Newspaper accounts said the girl was rushing to make it to school for a class trip.

In both the Steve Mayer and Blanca Hernandez cases, the drivers responsible for the crash were said to be devastated. The Robbinsville High School student was taken to counseling, and was eventually sentenced to three years of probation for careless driving and leaving the scene of a fatal crash. Thousands of people came to a vigil for Mayer.

Hernandez was charged with allowing Blanca to ride without a seat belt, running a red light, and going straight in a left-turn lane, but police did not charge him under the law that prohibits using a cell phone while driving. “He dropped something — it would be as if he bent down to get a cup of coffee that had dropped,” a report said. “He was distracted when he went through the intersection.”

In South Jersey, the effects of a 2012 collision can still be felt. Nikki Kellenyi, an 18-year-old high school student in Blackwood, was looking forward to her prom one afternoon while out on a drive with friends. She was sitting in the back seat of a Saturn driven by her high school friend. Another friend was sitting in the front seat. Kellenyi was the only one of the three girls wearing a seat belt. The car turned left across three lanes of traffic and into a Ford F-150 pickup truck. The front seat passenger was thrown from the wreck and spent several days in the hospital. Kellenyi was trapped in the car and died an hour later when rescuers freed her from the wreckage. The driver was unscrathed.

The teen driver pled guilty to driving with an open container of alcohol and failure to stop at a stop sign, and lost her driver’s license for six months. Prosecutors were never able to prove whether she was texting or talking on her phone at the time of the crash, but Nikki's father, Mike Kellenyi, blames distracted driving for the loss of his daughter. He says phone records show the driver had sent 1,500 texts the day of the crash including four in the minute leading up to it.

Kellenyi says the driver’s boyfriend’s phone had voicemail recording from Nikki that began moments after the crash. On his web page, Kellenyi describes listening to the message, which he says was deleted before it could be used in court:

“The boyfriend played it for Nikki’s family the next day, along with about 25 of Nikki’s friends. A six-minute recording that began a split second after impact. They listened to an eerie silence that lasted about a second, then the passenger, who was ejected started screaming, all the driver kept asking was ‘where is my phone, I can't find my phone?’ Then Nikki begging for help. At that point Nikki’s father had to stop listening.”

The Road Forward

To this day, there is fury in Mike Kellenyi’s voice when he talks about distracted driving. He can't get away from it. He works in construction, putting up overhead signs and guardrails all day. From his perch overhead, or from the cab of the equipment he uses, or from a high-riding truck, he can see right down into people's cars. He can see the phones, held in hands or resting on laps awaiting the next text message.

At first he would confront these drivers, wave his arms, and yelland tell them what their habit did to Nikki. But soon he realized he was only creating one more distraction on the road. Now he records video of them and posts it on Facebook or calls the police.

About three months after the crash, Kellenyi and his wife had the idea to launch an organization dedicated to assisting the victims of distracted driving and to putting a stop to it. “We were just devastated, and there was no one to turn to,” Kellenyi says. Victims of drunk drivers could turn to Mothers Against Drunk Driving for support and advocacy. But there was no such group for distracted driving. The couple decided to launch one, emulating the MADD model, and People Against Distracted Driving was born.

Founded in 1980 by the mother of a 13-year-old girl killed by a drunk driver, MADD is one of the most successful advocacy groups in history. The organization is credited with leading the way in changing both cultural attitudes and laws related to drunk driving, stigmatizing and criminalizing it nation-wide, and leading to a 50 percent reduction in drunk driving.

“We're the MADD of distracted driving,” Kellenyi says. “Distracted driving has taken over drunk driving as the number one killer of teens in America. I know it's also the number one killer in all traffic crashes, but it's too hard to prove and takes too much time, so the police don't bother prosecuting it.”

Kellenyi says PADD (www.padd.org) has now reached the grim milestone of helping 1,000 families who were victimized by distracted driving. It has also succeeded in gettirig “Nikki's Law” passed, which mandated putting up signs on state roads warning against distracted driving.

In 2016, months after Steve Mayer's death, the New Jersey state legislature advanced a bill that would put a “U-Text, U-Drive, U-Pay” message on inspection stickers of cars all over the state, reminding drivers of the penaltieS for being caught texting behind the wheel. There is a $200 to $400 penalty for the first texting while driving offense, which scales to up to $800, 90-day loss of license, and three license points for the third offense.

In a strange coincidence, the bill was inspired by the Robbinsville chapter of the Students Against Destructive Decisions club, which meets after school to advocate for safe driving and against drug use and other activities that put teens at risk.

Distracted driving is the top killer of teens and is likely the top killer in all traffic crashes, Mike Kellenyi says, but it's difficult to prove and thus not always prosecuted.

The students actually had put the law forward in 2014. The club's advisor, chemistry teacher Jennifer Allessio, helped the students work with Assemblyman Wayne DeAngelo to get the bill introduced as part of a collaboration with the Brain Injury Alliance. That same year, the club launched a driving safety campaign within the school with the slogan, “Wait to Text.”

After Mayer's death, the club backed off the campaign for the rest of the school year. “We don't feel as though the school community right now should be bombarded with any messages about texting and driving,” Allessio says. “The student involved in the accident wanted privacy.” The student is no longer at the school, but out of sensitivity to her family and friends, the school is treating the issue delicately. The new slogan, “Drive Like a Raven,” (the school mascot being a raven) emphasizes overall good driving habits. It seems no one at Robbinsville needs a reminder about the damage distracted driving can do.

But what, exactly, is distracted driving? Here, the law and the science are not in alignment. Currently, New Jersey law is narrow. For drivers over 21, it bans texting and playing video games while driving but allows talking on hands-free devices. State Assemblyman John Wisniewski, the chairman of the Transportation and Independent Authorities Committee, has introduced a broader law that would allow police to ticket drivers for doing anything “unrelated to the operation of the vehicle, in a manner that interferes with the safe operation of the vehicle.” (The law has met with opposition and criticism that it would prohibit drivers from “drinking coffee,” but Wisniewski says that's not the intent.)

Although talking on hands-free devices is currently allowed by law, studies have shown that even using a Bluetooth phone can divert drivers' attention from the road. The National Safety Council says the distraction of paying attention to the conversation, not merely the tying up of hands, is what makes driving while talking on a cell phone dangerous. The brain can only do so many things at once, and multitasking degrades performance dramatically. In a report, the group compiled the results of 30 scientific studies comparing the safety of driving while talking on hands-free phones versus handheld phones. In various ways, the studies showed drivers' performance plunging when using hands-free devices.

Transport Canada had drivers talk on hands-free phones and then tracked their eye movements. Then they repeated the experiment with no cell phone at all. The eye trackers showed that undistracted drivers looked at an area covering most of the windshield, but when engaged in a conversation, they focused on a tiny area in the middle of their vision, about the size of a textbook on the windshield. They also looked at their mirrors and instruments less and some even ignored traffic signals at intersections.

A University of Utah driving simulator study found that when talking on cell phones, drivers’ re-flexes were delayed just as much as someone driving at the legal intoxication limit.

Other studies showed that drivers were four times more likely to crash when talking on hands-free cell phone than when they were not.

Because of studies like this, some organizations have taken a hard line stance against talking on the phone while driving, even with hands-free devices. The National Fleet Management Association, (NAFA) a Forrestal Village-based trade group for companies that operate fleets of trucks, buses, vans, cars, and other vehicles, recently drafted strict rules for its employees, contractors, and volunteers (see sidebar, page above). The rules forbid them from using any per-sonal electronic devices while driving any vehicle.

The group encourages all its members to adopt the same stance.

Nationwide, there were 1.08 deaths per 100 million miles traveled in 2014, a number that has been on a downward trend since the 1990s. (Statistics for 2015 and 2016 are unavailable.) An increase in driving due to an improving economy and lower gas prices may account for some of the increased number of traffic deaths. One clear statistic is that the overall number of deaths in New Jersey had been on the decline since 1996 before the sudden reversal in 2013.

David Thompsen, chair of NAFA’s safety advisory council, says this year’s sharp increase in highway fatalities was a wake-up call for the industry. He blames the rise in deaths on people being more tied to their phones than ever before, and not just drivers. “Like when you had the Pokemon craze, holy crap, not only were the drivers distracted, but now the pedestrians were walking around distracted. They weren’t even looking at cars coming at them,” he says.

Attempts are being made to create a technological solution for the technology-induced problem of cell phone use behind the wheel, but some believe that more technology will only add to the problem.

Thompsen says there is a debate within the transportation industry about efficiency versus safety. Many transportation companies currently use cell phones to contact their drivers while they are en route. NAFA has come down hard on the “safety” side of the discussion.

NAFA’s goal is to spread the safety-first attitude to transportation companies nationwide. “It’s been received pretty well by most people,” he says. “A company’s attitude about it comes from the top down.” He says he once visited a company that had anti cell phone rules, but no one followed them because the CEO was frequently seen talking on the phone while driving.

Attempts are being made to create a technologioal solutionlor the technology-induced problem of cell phone use behind the wheel. Smartphone apps exist that can disable certain cell phone functions if the phone is aboard a moving car. More sophisticated systems are being designed that can tell where a phone is within the car, so passengers can still use their phones but the driver is cut off.

Thompsen says some railroads use devices in the cabs of their locomotives that block all cell phone signals.

But Thompsen believes technology will make the problem worse before making it better. New cars include increasingly sophisticated “infotainment” systems, and phones get more distracting all the time. “We have to try to find a solution before the rates keep going up,” he says. “I would say distraction is the leading cause of most motor vehicle collisions. For us, it’s just ‘take all that stuff away and just try to drive, and when you get to your destination, get on your cell phone and do your business.’ We are trying to lead by example.”

While NAFA is working within industries that employ commercial drivers, other groups are pushing for tougher laws that would curb the problem in the general public.

Mike Kellenyi, following MADD’s example, wants to bring distracted driving penalties in line with the punishments for DWI. He is pushing for laws on the state level, and has also begun working with Washington lobbyists to take the crusade national. He says texting drivers are stopped an average of three times before they even get a ticket, and he wants the leniency to end.

“I think the first offense should be a $3,000 fine and a four-point loss on your license,” he says. “It would do exactly what the laws did for drunk driving. You still have drunk drivers out there, but many people are worried about being pulled over. They are not worried about drinking and driving and hurting someone, but they are worried about drinking and driving and losing their license.”

Kellenyi is spreading the word on the Internet, with media appearances, and with organized events. He has put his anti distracted driving message on trucks that bear huge photos of a smiling Nikki. It’s the best way Kellenyi can think of to get his message across.

He still fights the urge to take matters into his own hands when he sees people texting or talking on the road. “I want to pull them out of their cars,” he says. “I want to yell and scream and cuss at them to get through to them. I lost my daughter.”

The Crash That Crushed a Face

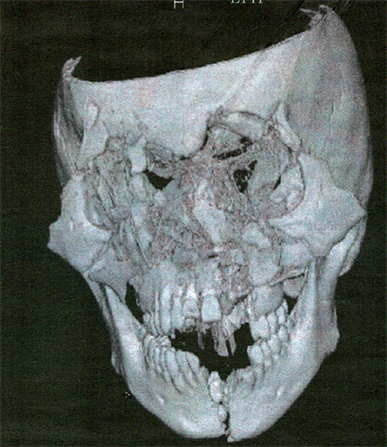

He Survived: When metal from a crash flew through Gabe Hurley's windshield, many bones in his face were shattered and he lost both eyes. Above is a CAT scan taken after the accident.

One night in 2009, Piscataway resident Gabe Hurley went driving in search of a 24-hour pharmacy where he could buy some toothpaste for a trip to Las Vegas. On his way home, at around 11 p.m., he was driving under an underpass in Edison when a teenage driver crashed into the bridge at about 60 or 70 miles per hour, sending metal flying in all directions. A 10-pound air conditioning compressor smashed through Hurley's windshield directly into his face.

Hurley woke up in the hospital a week later remembering nothing of the crash. “I lost both of my eyes, and my face split open,” he says. “If you look at a CAT scan, you will notice every bone in the middle of my face was sawdust. That's the level of trauma as the surgeon described it. The fact that I live, and am even able to speak, is a miracle.”

The driver who caused the accident was part of a group of 10 teenagers in four cars. Hurley says the Edison police could never prove distracted driving, but that with so many adolescents together out for a late-night drive, it was inevitable.

Hurley's crash left him blind, disabled, and with $1 million in medical bills. In 2009 he had recently graduated from college and was doing tech support at Virgin Mobile headquarters in Warren. He had planned to go back to school to earn a master's degree in forensics.

The collision changed Hurley's life but did not destroy it. Today he travels around the state giving presentations to high school students about driving safely. He tells the story of what happens to him, wrenching details included, but ends his talks on a positive note by showing off his guitar skills, which have fully returned. “I can shred like Van Halen, so I do a guitar medley at the end of the presentation,” he says. Hurley has rejoined the band he played with in his former life. Currently he is focused on his music and raising awareness of distracted driving.

He tells the students that each one of them “has the power to stop

this from happening” by driving safely. Even as a passenger, a sensible person can speak up and be the voice of reason that stops a trag-edy in the making. Hurley wishes someone like that had been there on the night he was injured. “Maybe the driver of that first car was a jerk and didn't care,” he says. “Still, there were other kids in that car who could have intervened and done something.”

— DICCON HYATT