by ILENE DUBE

In 1991, when Princeton University Art Museum exhibited “Minor White: The Eye That Shapes,” I attended a gallery talk given by Peter C. Bunnell, former curator of photography and author of “Aperture Magazine Anthology: The Minor White Years, 1952-1976.” Bunnell, who met White when he studied with him at the Rochester Institute of Technology in 1955, recounted something White had said that was so inspirational I jotted it in a journal. The problem with journals is they are not searchable, and I rely on a flawed memory to paraphrase: Early in his career, White hungered to possess his subject matter. Later, he learned he could be satisfied photographing them. Finally, he knew it was enough to see.

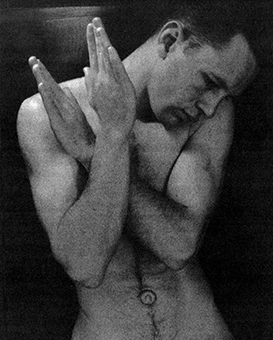

Untitled photograph by Minor White.

Now there is a new tool to help scholars and art lovers find information about White (1908-1976), one of the major figures of American photography in the three decades following World War II and a key figure in shaping a distinctly modern American photographic style. Princeton University Art Museum has released the Minor White Archive at artmuseum.princeton.edu/minor-white-archive. Funded in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the digitization and cataloging project began in 2014 and includes more than 6,000 finished prints, negatives, proofs, contact sheets, journals, library, correspondence, ephemera, and bibliographic history.

The archive came to Princeton as a gift of the artist in 1976. With future support, the entire archive of more than 26,000 assets (including 19,000 artist's negatives and 7,000 undocumented finished photographs, as well as the artist’s entire archive of correspondence, personal and published writings, and exhibition notes) will be made available on-line, serving as the single most comprehensive guide to White’s photographic process and career.

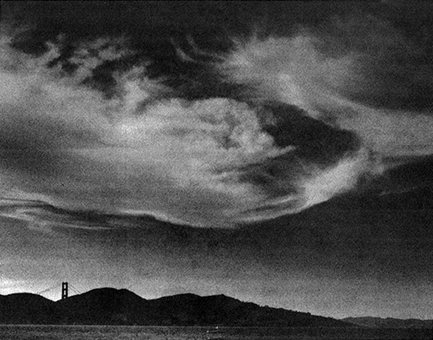

Untitled photograph by Minor White.

White's archive entered the museum’s collections during the nearly 30-year tenure of curator Bunnell. “Minor White: The Eye That Shapes,” the exhibition Bunnell curated more than a quarter century ago, interpreted White’s photographic achievements in relation to past photographers such as Alfred Stieglitz, Ansel Adams, and Paul Strand, and traveled to New York's Museum of Modern Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

A resurgence of interest in Minor White's work has led to several newer exhibitions: “Minor White: Poetic Form” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (2013); the J. Paul Getty Museum's sweeping career retrospective and accompanying publication (2014); and a major touring exhibition organized by the Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego (2015-'16). All have been facilitated by the resources of the Minor White Archive at the Princeton University Art Museum.

Just before the Getty exhibition opened, Bunnell recounted his years as White's student at Rochester to Katherine A. Bussard, the curator of photography at Princeton University Art Museum, where White held informal sessions where he explored in more depth his philosophy and attitude toward photography. “In this context I became close to him on a more personal level, and I be-came his assistant on Aperture magazine, which he edited,” Bunnell told Bussard. “When I came to Princeton in 1972, he was excited about the program we were developing in the Department of Art and Archaeology and in the art museum. Minor visited campus a few times, lectured here, and conducted seminars. With knowledge of the program and of my background, he decided that he would bequeath his archive to Princeton, indicating in his will that I was to be responsible for it.”

Over the years, many institutions have requested loans from the archive, and there has been an increasing interest in reprinting White’s writing.

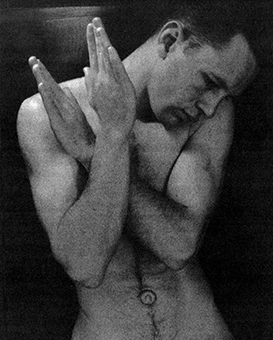

During his lifetime White made thousands of black-and-white and color photographs of landscapes, people, and abstract subject matter, created with both technical mastery and a strong visual sense of light and shadow. His wide-ranging subject matter included portraiture, studies of the nude, landscape, and architecture. His work evolved into biomorphic abstraction.

Untitled photograph by Minor White.

White was born in Minneapolis to a bookkeeper and dressmaker. His grandfather, George Martin, was an amateur photographer. When Minor's parents were splitting up, he lived with his grandparents and, in 1915, Martin gave White his first camera. At the University of Minnesota, White studied botany, literature, and poetry and learned the basics of photography through photomicrography transparencies of algae.

White made thousands of black-and-white and color photographs of landscapes, people, and abstract subject matter, created with both technical mastery and a strong visual sense of light and shadow.

He began his photographic career in 1937 in Portland, Oregon, photographing architecture and gaining technical expertise in theater and landscape photography before being drafted into the U.S. Army.

White spent the first two years of World War II in Hawaii and in Australia, writing poetry and doing very little photography. He believed that all photographs were self-portraits, and photography and poetry came from the same place, seeking to grasp the spirit.

After the war White went to New York City to learn museum curatorial procedures with Beaumont and Nancy Newhall at the Museum of Modern Art. He studied art history under Meyer Schapiro at Columbia University, and in 1946 he joined Ansel Adams on the faculty of the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco. He went on to teach at Rochester Institute of Technology and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

In a famous exchange between Alfred Stieglitz and White early in White's career, when White asked if he could be a photographer, Stieglitz replied, “Well, have you ever been in love?” White said “Yes,” and Stieglitz responded “Then you can be a photographer.”

Yet White lived much of his life as a closeted gay man, afraid to express himself publicly for fear of losing his teaching jobs, and some of his most compelling images are figure studies of men whom he taught or with whom he had relationships.

“White consistently sought to universalize his suffering, drawing on literature, psychoanalysis, and myriad spiritual texts to cope with his particular perspective on the human condition,” writes curator Kevin Moore at Aperture, where White was founding editor. “But his sexuality remained a thorn in his side. Moreover, it was something he felt compelled to express, despite fears of persecution and rejection.”

Tormented by forbidden desire, White inherited the modern photography mantle of Stieglitz and Edward Weston, who often focused their lenses on the female form. “For all White's efforts at emulation, his photography could not sustain the optical machismo of his forebears; it could not continue in the prescribed modernist tradition,” writes Moore.

After White's father died in 1952 he was introduced to the I Ching and became inter-ested in concepts of yin and yang. While at RIT he began practicing Zen meditation and explored the philosophy of mystic George Gurdjieff. White made a sequence of images, “Sound of One Hand,” a summation of his persistent search for a way to communicate ecstasy.

In 1969 White published “Mirrors, Messages, Manifestations,” which included 243 of his photographs supplemented with poems, notes from his journal, and other writings; Bunnell wrote White's biography for it. “Often while traveling with a camera we arrive just as the sun slips over the horizon of a moment, too late to expose film, only time enough to expose our hearts,” wrote White.

“Minor White believed that photography has the potential to spiritually transform the viewer as well as the practitioner,” writes the Getty Museum's Chris Keledjian. Photography became both a way to make visible White's ongoing search for spiritual transcendence and a medium through which he could express his sexual desire for men.

I never could find that quote I found so inspirational all those years ago, but here are a few I did find that convey the same spirit:

“... innocence of eye has a quality of its own. It means to see as a child sees, with freshness and acknowledgment of the wonder; it also means to see as an adult sees who has gone full circle and once again sees as a child — with freshness and an even deeper sense of wonder.”

“When I looked at things for what they are I was fool enough to persist in my folly and found that each photograph was a mirror of my Self.”

“I'm always mentally photographing everything as practice.”

“When gifts are given to me through my camera, I accept them graciously.”

Princeton University Art Museum, artmuseum.princeton.edu/minor-white-archive