PERSPECTIVES

MARC RUSKIN

FBI agents are very smart—a characteristic not fully appreciated by politicians, journalists, and many a wrongdoer, from brilliant financiers to Mafia dons, whose underestimation of their adversaries resulted in long prison sentences. And FBI agents have tough skins; their feelings are not easily hurt.

President Trump launched a media and Twitter assault on FBI executives in mid-December, following the disclosure of the now infamous Strzok-Page text exchanges. Predictably, self-serving journalists and politicians have loudly worried—just as they did when President Trump fired the former bureau director James Comey last year—about the morale of the bureau’s special agents.

WIN MCNAMEE/GETTY IMAGES

FBI Director Robert Mueller testifies before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Capitol Hill on Dec. 14, 2011.

Forgotten for the moment, apparently, are the pre-election accusations by pundits of an FBI cabal in New York, represented by that office’s former chief, James Kallstrom, posedly plotting to enthrone candidate Trump as president.

FBI Director Christopher Wray’s removal of Andrew McCabe from the No. 2 position on Jan. 29 sent a clear message of his commitment to clean house.

A parade of FBI upper management, active and retired, has taken its cue and assured the world that the morale of the agent population has not suffered another “gut punch,” or, in the words of Trump, been reduced to “tatters.” And politicians and commentators have expressed hitherto unrevealed concerns for the feelings of the nation's toughest law enforcers.

But these denizens of the FBI’s executive suite are the wrong people to ask. The special agents themselves are certainly dismayed to find themselves occupying a place at the center of the current political maelstrom. I have served under four directors, and I can state with some assurance that defending the bureau’s integrity and political independence is of paramount importance to the agent population.

Though they may be dismayed at being questioned by acquaintances about the bureau’s tarnished reputation, the agents understand who is under attack; and they know that it is not the rank and file.

To fully understand what is happening inside the FBI, one should be aware of a few key characteristics of this unique institution.

There are two distinct cultures within “The Bu,” as it is affectionately called by those who work there. These is the agent culture, consisting of field agents, street agents, and case agents: These are the men and women who risk their lives, investigate cases, and protect you. Then there is the management culture, made up of those who long ago exchanged the street for the desk, and whose greatest risk is making decisions that might impair or even derail their ascension to the next level of the Bu’s hierarchy.

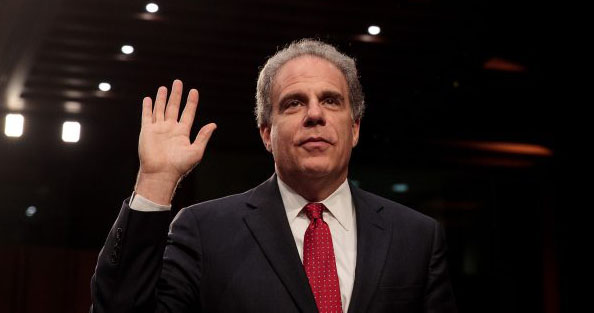

DREW ANGERER/GETTY IMAGES

Michael Horowitz, inspector general of the Justice Department, on Capitol Hill on July 26, 2017.

Most agents have no interest in moving up that ladder. They aspire instead to bigger, more complex, and increasingly challenging cases in the field that offer higher profile targets and expanding responsibility. Agents with less street sense, minimal rapport-building skills, and those who are perhaps concerned for their own physical safety—well, these folks go into management. Are there good managers? Of course—but they are the exceptions—not the rule.

There is a deeply rooted distrust between these two cultures, with street agents generally believing the mission of upper-level managers is to impede their work. So when the White House condemns the purportedly political decision-making on the seventh floor of FBI HQ—the executive suite—the rank and file are hardly likely to see themselves as being in the crosshairs.

On the contrary, the buzz from onboard and retired agents—field agents—reveals a profound concern that their cherished institution has been dragged from its premier position as the objective and neutral arm of justice and turned into a partisan enforcer of political ends.

The agents understand who is under attack, and they know that it is not the rank-and-file.

They see the shift as beginning July 5, 2016, with the now infamous “Clinton server” news conference, in which then-Director Comey announced that “no reasonable prosecutor” would press charges with regard to the voluminous classified emails found in then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s unofficial, unsecured, and unclassified home computer network.

Everyone knows, now, after ceaseless repetition, that the Bu only investigates: It does not decide whether to prosecute. That decision is left to the Department of Justice.

The perception of politicization has been strengthened by recent revelations that an FBI executive, Peter Strzok, had edited—changed—the director’s characterization of Secretary Clinton’s acts from “grossly negligent” (i.e. criminal) to “extremely careless.”

Curiously, the media has downplayed Strzok’s prominence in the management hierarchy, generally referring to him simply as a special agent, essentially an errand boy. He was in fact—at least until recently—a deputy assistant director, a boss, a decision maker. Therefore, his activities take on an ominous significance.

He was redrafting directorial pronouncements, drafting emails characterizing the president of the United States as “an idiot,” engaging actively in conversations with now-former Deputy Director Andrew McCabe and now former FBI Counsel Lisa Page, in which they were arguably attempting to influence the outcome of the presidential election—Hoover’s legacy has been betrayed.

Yet the bureau’s reopening of the Clinton Foundation investigation may signal a sea change, a return to the tradition of public corruption investigations unfettered by political influence and unintimidated by the prominence of those under examination.

CHIP SOMODEVILLA/GETTY IMAGES

The official seal of the FBI at the J. Edgar Hoover FBI Building in Washington in 2016.

DOJ Inspector General Michael Horowitz appears to have already initiated the requisite house cleaning. FBI Director Christopher Wray and special counsel (and former bureau Director) Robert Mueller, are likewise committed to seeking truth, wherever it may lie.

Wray’s removal of McCabe from the No. 2 position on Jan. 29 sent a clear message of his commitment to clean house. A concerted effort can indeed restore the FBI to its historic prominence as the global model for objective, impartial, and ultra-competent law enforcement—the sine qua non of a democratic republic. This, and only this, will guarantee that high level of morale characteristic of FBI personnel.

Marc Ruskin, a 27-year FBI veteran, is author of “The Pretender: My Life Undercover for the FBI,” published by Thomas Dunne Books, an imprint of St. Martin’s Press. He served on the legislative staff of U.S. Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan and as an assistant district attorney in Brooklyn, New York.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.