BLACK HISTORY MONTH

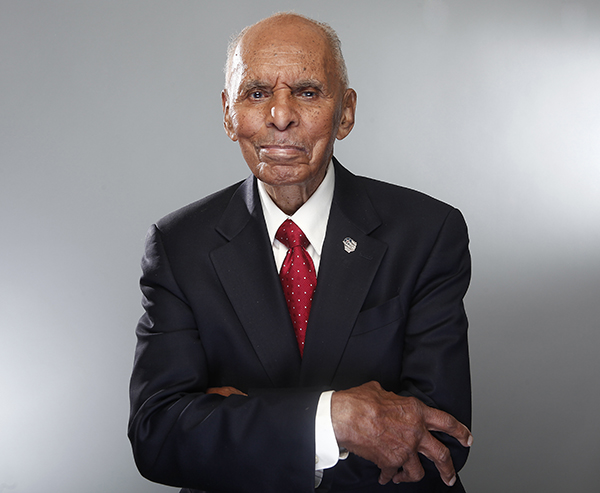

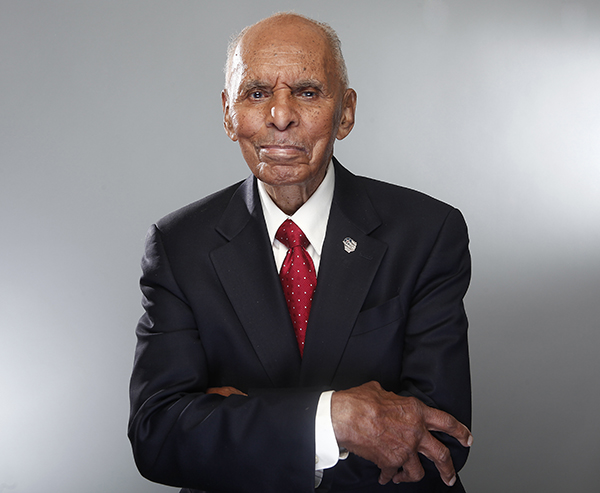

AP PHOTO/CARLO ALLEGRI

Roscoe Brown during the “Red Tails” pres junket i New York 2012. “Red Tails” is a film that chronicles the heroism of the Tuskegee Airmen.

By Charlotte Cuthbertson I Epoch Times Staff

NEW YORK—Lynda Hamilton was 12 the first time she met the unstoppable Roscoe Brown Jr.

Hamilton’s aunt had invited Brown to their annual family Christmas tree-trimming party. “Roscoe came religiously every year from that point on. He was the center of these parties,” Hamilton recalled on Jan. 27, six months after Brown died at age 94.

“He talked to you like you matter,” Hamilton said.

Now 52, Hamilton is bursting with stories about the man whom she considered her best friend. “When I needed him, he was there, and he was always loving. He was unconditionally loving to me and my family.”

Brown lived by the motto “three P’s equals E,” or preparation, persistence, and pride equals excellence.

“That drove him. He would talk about it until the day he died,” Hamilton said.

During World War II, Brown was an accomplished member of the Tuskegee Airmen, a group of 994 African-American pilots who were famous for their heroism escorting American bombers over Europe and North Africa.

At age 22, Brown became a captain. He flew 68 combat missions and was credited with being the first Tuskegee airman to shoot down a German bomber. He earned the Distinguished Flying Cross.

AIR FORCE HISTORICAL RESEARCH AGENCY

Tuskegee Airman Roscoe Brown completed 68 combat missions during World War II.

But Brown and his airmen weren't just fighting a war abroad: The Jim Crow laws were still in effect at home, and they faced segregation and vitriol even within the armed forces.

“He had a lot of frustrations about those things at that time, and they [airmen] would knock up against it, they would challenge it. They would go where they weren’t supposed to go,” like the mess hall and social areas, Hamilton said.

Roscoe Brown

RAN NINE

NEW YORK CITY

MARATHONS

the first when he was 57.

He ran his fastest time

(4:38:37) when he was 61.

“He would tell me stories, ‘We went there any-way and made them throw us out and think about what they did.’”

It wasn’t until 2007, when Brown was 85, that he and five other Tuskegee Airmen were awarded a Con-gressional Gold Medal—the nation’s highest expres-sion of appreciation—on behalf of the group.

“Even the Nazis asked why African-American men would fight for a country that treated them so unfairly,” said President George W. Bush in awarding the medals.

“These men in our presence felt a special sense of urgency They were fighting two wars. One was in Europe, and the other took place in the hearts and minds of our citizens,” he said.

The Tuskegee Airmen were credited with helping end segregation in the armed forces. Many of the airmen, including Brown, continued their activism post-war and helped usher in the civil rights movement.

After the war, Brown wanted to become a commercial pilot and applied to all of the commercial airlines.

“All of them rejected him. And he was very frustrated, he was very angry,” she said. “Racism kept him out of the airline industry after being a hero. It was very hard for all of them.”

Brown went into education instead.

“The core of what drove him was the future,” Hamilton said.

COURTESY OF LYNDA HAMILTON

Roscoe Brown (R) and Lynda Hamilton attend the renaming event for the David N. Dinkins Municipal Building on Oct. 15, 2015.

Brown became a professor at New York University after completing his doctoral dissertation in exercise physiology. A tireless champion for civil rights, he also directed NYU's Institute of African-American Affairs.

From 1977 to 1993, Brown was president of Bronx Community College, after which he became director for the Institute for Education Policy at the City University of New York.

When Hamilton got divorced in 1999, Brown hired her and a deeper connection was formed between the two.

“You learn a lot just by watching someone that classy get in the trenches and how they get things done,” she said. Roscoe was never at the forefront or the troublemaker, she said. Rather, he managed to steer progress quietly.

Brown was an adviser to New York City Mayor David Dinkins (1990-1993), and he rubbed shoulders with Congress members, governors, educators, and activists.

Hamilton helped Brown manage all of his approximately 30 board memberships. “He was dedicated to all of them,” she said. The boards included parks organizations, athletics organizations, services for the elderly, and educational organizations.

“He got viewpoints to change,” Hamilton said.

“There was always this mysterious power and persuasion that Roscoe had. When the tides really turned, it was these quiet moments with him behind a closed door on a phone that most of us didn’t we.”

Hamilton described his hopeful spirit. “He was just going to keep learning because he was never going to die,” she said. “He just would not stop and he didn’t see a reason why he had to.”

But Brown was 94, and although his mind was sharp, his body was winding down. He had a pacemaker and then he broke his hip.

“He was in bed, he had a broken hip, he had a problem with his foot, he had the scars on his head, he had one eye. It was really like a warrior going down and still fighting,” Hamilton said.

Hamilton is still guided by Brown’s wisdom; he is still mentoring her, reminding her that “three P’s equals E,” and helping her strive to be a better person.

Brown is survived by his sons Dennis and Donald, and two daughters, Doris Bodine and Dianne McDougall. He will be interned at Arlington Cemetery on his birthday, March 9.